Trauma and coping with trauma: Dealing with the consequences of violence

Trauma that was caused by sexualised violence is more than just a psychological or physical injury. In particular, the social consequences run deep, so counter-measures need to be taken at the level of society, by acknowledging the suffering of and demonstrating solidarity with survivors, and by prosecuting the perpetrators.

After traumatic experiences of violence, it is possible for individuals to regain stability, security and trust in relation to other people. The work of medica mondiale and local partner organisations has shown this. At the same time, medica mondiale is trying to prevent the pathologisation of affected people by drawing attention beyond these impacts to the experiences of violence that caused them. What is needed for this to succeed?

FAQ: Trauma

Trauma is an issue which is becoming the subject of widespread and diverse awareness in many fields, including international co-operation. Here we will take some of the key terms most relevant to project work on sexualised violence and trauma, explaining them from the perspective taken by medica mondiale.

What is psychological trauma?

A psychological trauma is “a psychological wound caused by one or more injuries to the body, integrity or dignity of the person. Trauma is not only caused by one powerful event (...) but arises as a process within the person’s surroundings, especially their close relationships. Traumatisation is the result of violence experienced either physically or psychologically, subtly or explicitly, once or frequently.” (Translated from source: Dileta Sequeira, ARIC, Erkennen lernen, 2019, p. 40)

What is stress?

Stress is part of our everyday life, when our body does everything it can to ensure it can perform quickly and readily to deal with a particular situation. This is noticeable due to physiological reactions such as the release of stress hormones, an increased pulse, quicker breathing or the tensing of muscles. When the situation is over, these stress reactions usually subside and we can return to a normal physiological state.

What is the difference between stress and trauma?

The usual physiological stress reaction ebbs away after the stressor situation finishes, with the body returning to its usual state (homeostasis). However, if the stress reaction system is overwhelmed, our subjective experience is that we can no longer cope. It is this inability to deal with the experience which characterises the process of trauma, leading to the secondary reactions of traumatisation.

How is trauma triggered?

When a person lives through or witnesses an event that triggers an existential threat, and when there is no opportunity to fight, to flee or to seek assistance, then the body switches into ‘emergency mode’ in order to ensure that the person survives. The normal processes which would then take place to deal with a stressful experience and return to a normal state are no longer able to take place. In this way, a deep psychological wound can be inflicted. And the person might continue to experience a persistent, elevated sense of stress.

What factors reinforce a traumatisation?

There are numerous factors which can exacerbate the traumatisation, such as prior experiences of trauma or violence, pre-existing psychological conditions, or the extent of the violence suffered. The impacts of traumatic experiences can also be made worse due to factors such as living in ongoing situations of insecurity, new attacks happening, humiliation or feelings of guilt or shame. The social surroundings also play a major role: reactions can vary from compassionate through shaming to accusing.

What are the symptoms of trauma?

Trauma symptoms can be understood as the residues of the traumatic experience that have not been successfully processed. These force their way into our consciousness and trigger emotional memories or nightmares. We start to avoid or suppress any thoughts, activities, people or situations that remind us of the events. The consequences of this include symptoms such as jumpiness, anxiety, difficulties in regulating emotion, (social) withdrawal, pain, memory lapses, negative self-esteem or a negative outlook on life.

How can we recognise if someone is suffering from trauma?

Psychological trauma manifests itself in various ways.

- There is a constant state of physical alert (hyper-arousal). This is recognisable because of sleep disturbances, jumpiness and difficulties in concentrating.

- The survivor has painful memories (intrusions), resulting in nightmares and persistent over-thinking.

- Avoidance or suppression of any thoughts, activities, people or situations that are reminiscent of the events.

- Emotional numbness or rigidity: the affected person withdraws and begins to lose hope.

What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

According to the current clinical definitions of the International Classification of Diseases published by the World Health Organisation (ICD-11 from 2019), PTSD is characterised by vivid intrusive images (re-experiencing the traumatic experience, triggered by a specific stimulus or nightmares), avoidance (of thoughts and memories, people, activities and situations) and hyper-arousal (heightened sense of threat).

What is a complex traumatisation (CPTSD)?

The WHO classification ICD-11 introduced the diagnosis of Complex PTSD as the consequences of multiple or chronic interpersonal violence. This diagnosis comprises the above-mentioned symptoms of PTSD and additional symptoms related to disturbances in self-organisation: affect dysregulation, negative self-concept (deep-seated feelings of guilt, shame and failure), and relationship issues (difficulties in entering and maintaining intimate relationships).

Is trauma an illness?

A psychological trauma is actually a normal reaction to abnormal events that are full of violence and that threaten our survival. Examples include sexualised or racist violence that needs to be experienced, assessed and processed subjectively. However, these reactions can lead to an impairment in our quality of life if they persist for a long time. This is why trauma reactions are defined within a clinical diagnosis: it allows appropriate treatment to be claimed and performed.

What is resilience?

In the field of psychology, resilience is the term used to describe our ability to cope with challenging circumstances such as emergency situations in an adaptive and integral way. The advantages of using this term lie in the emphasis of the capacities, resources and creativity we are endowed with as humans. The potential inherent in these resources does depend on the individual, and the experiences that person has lived through in their social surroundings and society as a whole.

What is retraumatisation?

Retraumatisation is the experience of another situation or event that the survivor associates with the original traumatic experience and therefore becomes traumatising. One example might be a gynaecological examination. This can lead to a significant deterioration in the survivor’s post-traumatic stress reactions.

How can retraumatisation be prevented?

By taking part in appropriate training, people helping survivors can gain an awareness of the trauma dynamics that can lead to retraumatisation, which in turn allows them to take pre-emptive measures. For example, during medical treatment it is important to remain in contact with the client and to be aware of possible symptoms of a retraumatisation such as quicker breathing or increased muscle tension. Then the helper can react accordingly.

What is secondary traumatisation?

Let us consider the example of counsellors: in the course of their work they listen empathically and compassionately to numerous descriptions of traumatic experiences, forming human connections to people who are suffering from the pain of trauma. This can all lead to them being affected in a similar way to people who experience violence directly and, for example, suffer similar symptoms such as nightmares or persistent heightened tension (hyper-arousal).

Is there such as thing as collective trauma?

Specific groups or even whole societies can have collective experiences of violence; examples of this are genocides, the Holocaust and colonialisation. These then lead to collective trauma. This is the case when the experiences of violence are not acknowledged and cannot be processed, and when they continue to have an impact as marginalisation (racism). The trauma reactions can be experienced collectively and passed on collectively (transgenerational).

What is meant by a ‘trigger’ or ‘triggering’?

Triggers can be emotional, physical, sensory or auditory stimuli. Triggers are stimuli or cues that suddenly cause stress and which have a direct connection to the stressful event. An example might be the smell of a fire, which could call up vivid memories of the unusual and stressful event for someone who had been trapped in a burning building. This person then experiences the same feelings of helplessness and powerlessness, despair, fear and loss of control that they experienced during the traumatic event in the past.

What is a dissociation?

The literal meaning of this word is to separate, to not connect, to distance oneself from something. Applied to trauma, dissociation is used to describe a mechanism used in cases where we are threatened and overwhelmed: the mechanism allows us to switch off our rational thinking patterns and focus on life-sustaining and species-preserving activities.” (Translated from source: Hantke/Görges 2012: Handbuch Traumakompetenz. Basiswissen für Therapie, Beratung und Pädagogik, p. 75 f.)

Does sexualised violence cause trauma?

In the American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), sexualised violence has been explicitly listed as a possibly traumatic event since 2013. Research suggests that over 50 per cent of those affected develop a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). An explanation for this is that those affected find themselves in an extraordinary situation that they experience as being threatening and shaming. Processing of this experience is then made difficult by society’s taboos, stigmatisation and blaming.

What characterises sexualised violence as a cause of trauma?

Sexualised violence is a particularly frequent cause of post-traumatic stress because it directly affects the most intimate self of a person. It is an invasive form of violence that violates the person’s integrity and is also subject of a taboo. Those affected are stigmatised and their suffering is not acknowledged. Sexualised violence is often an expression of emotional and economic power imbalances. This can also make it more difficult to process the violence.

What characterises sexualised wartime violence as a cause of trauma?

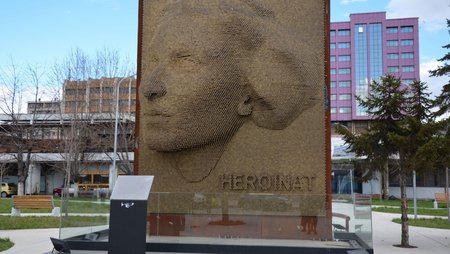

In sexualised wartime violence, the sexualised violence is used as a collective weapon of war in order to destroy families, communities and social cohesion. Studies have shown that the incidence of sexualised violence increases during phases of escalation in a conflict. As part of a military strategy, the aims are to humiliate and shame the enemy groups, to degrade people, and to force them to flee.

How does medica mondiale understand trauma?

medica mondiale has a feminist and socio-political understanding of trauma. This is broader than merely looking at trauma as something suffered by the individual person: We always include violence as a cause of traumatisation, and we consider the social and societal conditions for coping with or processing trauma. We see post-traumatic stress reactions as strategies for survival and defence when faced with violence, threats and oppression.

FAQ: Dealing with the consequences of trauma

Although trauma processes are a normal reaction to intolerable and abnormal experiences being inflicted upon the survivor, these consequences of trauma can be dysfunctional. From the viewpoint adopted by medica mondiale and its project partners, when dealing with the consequences of trauma, beneficial impacts can be seen from adopting an approach that is both relationship-oriented and political. A selection of common questions about this approach are answered here.

Therapeutic work distinguishes between three phases: stabilisation, processing and integration. The closing phase is when experiences can be integrated at the physiological, psychological and social levels. One indication that a trauma can be considered as ‘integrated’, ‘processed’ or ‘coped with’ is when the affected person can narrate the events they experienced as a coherent, complete tale without being overwhelmed by or having to suppress the feelings associated with those experiences.

Work to process trauma is divided into phases, which should only be considered as a general orientation.

- Stabilisation: The survivor learns to become aware of when their stress level rises, and how they can ground and calm themselves.

- Processing (exposition, confrontation): It is necessary for the survivor to have stability and support before starting this second phase of facing the traumatic events.

- Integration: The experience is stored in our biographical memory.

Within the internationally recognised Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support, two different approaches can be seen to indirectly reflect each other: One is a “medical/psychiatric” approach focused on the treatment of post-traumatic symptoms by helping the survivor in a therapeutic setting to confront what they experienced. The other is a relationship-oriented and political approach which assesses and identifies the traumatic reactions of survivors as a normal consequence of unbearable experiences and violations of their human rights. The usual post-traumatic symptoms are considered more broadly, and this approach also acknowledges the entire reality of people affected by violence.

Trauma therapy generally involves three phases of processing trauma. In Western research it is a widespread medical-psychiatric concept that focusses on treating the post-traumatic symptoms by providing a setting to help the survivor face what they experienced. This approach includes several factors or change mechanisms identified by research as being effective (here as listed by Klaus Grawe, 2004):

1) the therapeutic bond

2) resource activation

3) problem activation

4) motivational clarification, and

5) mastery (or problem-solving).

What is psychosocial counselling?

Psychosocial counselling comprises measures, actions and processes that enhance the integrated feeling of well-being of people situated within their social surroundings, helping them to deal with everyday challenges and any social conflicts and stressors related to this. This approach always starts with the resources currently available to each affected person, but considers this at both the individual and the collective levels.

Fundamentally beneficial factors include the regaining of a sense of security, social connections, and education about the possible consequences of traumatic experiences. When dealing with the impacts of trauma, medica mondiale takes into account the entirety of an affected person’s reality. These include fragile or precarious aspects of their social or economic situations, as well as their psychological or physical problems. The principles of the Stress- and Trauma-sensitive Approach (STA) are designed to stabilise and strengthen survivors, and to protect them from retraumatisation.

medica mondiale has a socio-political understanding of trauma. When dealing with the impacts of trauma, the political and social causes are always considered. This helps to avoid seeing trauma symptoms as pathological or the traumatic experiences as exclusively individual. The people affected can be helped to cope with what they experienced when there is acknowledgement of both the reactions to the trauma and the violence that was experienced and led to the trauma.

This concept was developed by Richard G. Tedeschi and Lawrence G. Calhoun, starting with their observation that in certain circumstances personal growth can actually succeed because of the experiences (rather than despite them). The conditions for this include becoming aware of their own strengths and (re-)gaining an appreciation of life.

“Being kind to oneself and feeling free to have fun and joy is not a frivolity in this field but a necessity without which one cannot fulfil one's professional obligations.”

Self-care means paying attention to our own physical, psychological and social health, as well as our feeling of well-being. And then acting accordingly. Measures and practices we can then adopt might be physical, psychological, emotional or spiritual.

What is the Stress- and Trauma-sensitive Approach (STA)?

The Stress- and Trauma-sensitive Approach (STA) is designed to ensure that survivors of sexualised and gender-based violence can receive expert support that is based on security, empowerment, solidarity and connection. It can be followed during counselling sessions, within communities, during the provision of services, and within institutions. The principles of this approach ensure it helps survivors to stabilise themselves and cope with their experiences.

Our trauma work for those affected by sexualised violence

For more than 25 years, medica mondiale has been assisting women and girls in and conflict areas who were affected by sexualised violence. One of our most important approaches to carrying out our work is to be active on both the individual and collective levels as we work to help people cope with the trauma caused by violence.

An example: community-oriented awareness raising and training.

Together with our partner organisations in, for example, Iraq-Kurdistan, we engage in community-oriented awareness raising and training for the police, legal and medical sectors to pursue our goal of creating an environment for survivors where they experience security and solidarity.

An example: Counselling in groups and one-to-one

Our partner organisation Medica Afghanistan worked within communities until the Taliban came to power in 2021, offering psychosocial counselling groups where women were able to talk to each other and learned methods to decrease stress and tension and to cope with the consequences of trauma. This was complemented by offers of one-to-one counselling. Some of the participants then went on to lead ‘peer groups’ in other communities, where they were able to inform participants of the rights of women and helped to refer people to further offers of support.

An example: Income-generating measures and family counselling

In Uganda, Liberia and Kosovo our partner organisations combine income-generating measures such as savings groups or work in a women’s agricultural co-operative founded by medica mondiale with low-threshold approaches to psychosocial empowerment. This might mean, for example, taking specific measures to enhance the personal connections and mutual trust within a group. In Rwanda and Kosovo counsellors will involve relatives such as husbands or children in order to explore the systemic impacts of trauma and violence, which helps to process the consequences of violence within the family system.

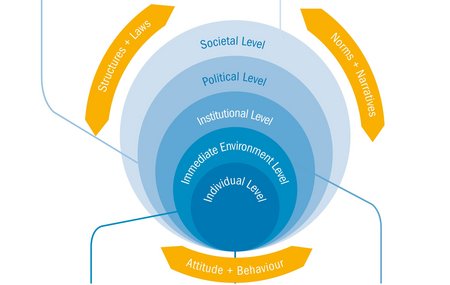

Trauma work: Implemented at more than one level

Unfortunately, many conflict areas do not have the conditions that would be important for dealing with the consequences of violence and for eliminating its causes. So in order to help women affected by violence find sufficient support anyway, medica mondiale has worked together with its partner organisations to develop a multi-level model that brings together direct assistance in the form of counselling and support with measures to enact change at the social, political and social levels. This approach is designed to ensure long-term beneficial effects in the surroundings of those affected. The particular expertise of medica mondiale lies in the promotion and funding of a Stress- and Trauma-sensitive Approach and solidarity measures which ensure that all the stakeholders and organisations involved receive support and gain a sense of security.